Here you will see the Riley v California case brief, as heard and decided together with the United States v. Wurie case.

Riley v California and the United States v. Wurie are landmark cases in U.S constitutional law.

Riley v California and United States v. Wurie cases declared searching and seizing the digital contents of a cell phone without a warrant during an arrest unconstitutional.

These two cases address a similar question: whether police can search digital information on a cell phone taken from an arrested person without a warrant.

Here I will share with you the case brief of the consolidated opinion of Riley v California and U.S. v. Wurie to help you understand everything you need to know about the Riley v California and the United States v. Wurie cases in a simple and accurate way.

Transform Your Communication, Elevate Your Career!

Ready to take your professional communication skills to new heights? Dive into the world of persuasive business correspondence with my latest book, “From Pen to Profit: The Ultimate Guide to Crafting Persuasive Business Correspondence.”

What You’ll Gain:

Interested in learning how to write your own case brief? learn here

Let’s get started

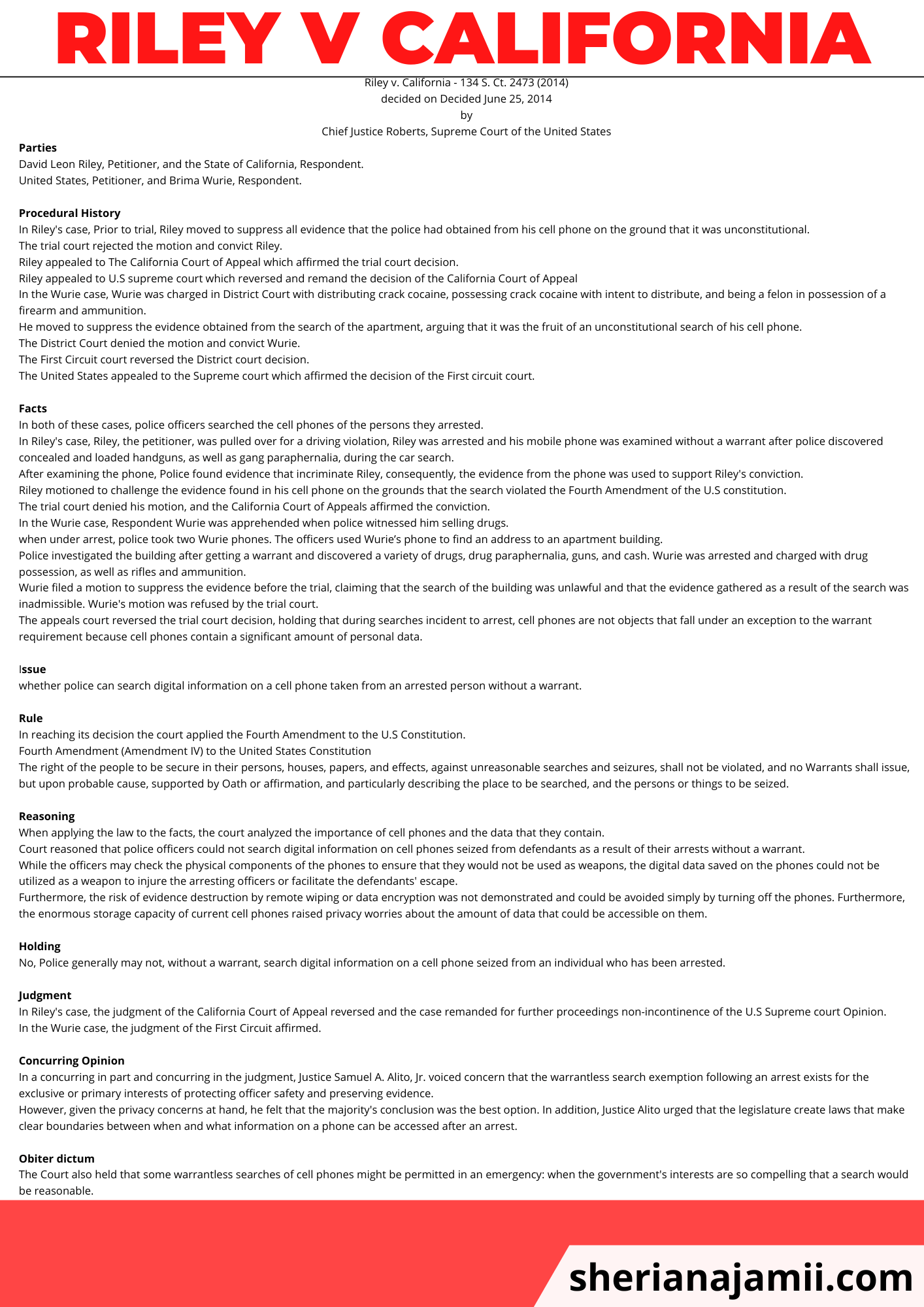

Riley v California case brief

Riley v. California – 134 S. Ct. 2473 (2014)

decided on Decided June 25, 2014

by

Chief Justice Roberts, Supreme Court of the United States

Parties

David Leon Riley, Petitioner, and the State of California, Respondent.

United States, Petitioner, and Brima Wurie, Respondent.

Procedural History

In Riley’s case, Prior to trial, Riley moved to suppress all evidence that the police had obtained from his cell phone on the ground that it was unconstitutional.

The trial court rejected the motion and convict Riley.

Riley appealed to The California Court of Appeal which affirmed the trial court decision.

Riley appealed to U.S supreme court which reversed and remand the decision of the California Court of Appeal

In the Wurie case, Wurie was charged in District Court with distributing crack cocaine, possessing crack cocaine with intent to distribute, and being a felon in possession of a firearm and ammunition.

He moved to suppress the evidence obtained from the search of the apartment, arguing that it was the fruit of an unconstitutional search of his cell phone.

The District Court denied the motion and convict Wurie.

The First Circuit court reversed the District court decision.

The United States appealed to the Supreme court which affirmed the decision of the First circuit court.

Facts

In both of these cases, police officers searched the cell phones of the persons they arrested.

In Riley’s case, Riley, the petitioner, was pulled over for a driving violation, Riley was arrested and his mobile phone was examined without a warrant after police discovered concealed and loaded handguns, as well as gang paraphernalia, during the car search.

After examining the phone, Police found evidence that incriminate Riley, consequently, the evidence from the phone was used to support Riley’s conviction.

Riley motioned to challenge the evidence found in his cell phone on the grounds that the search violated the Fourth Amendment of the U.S constitution.

The trial court denied his motion, and the California Court of Appeals affirmed the conviction.

In the Wurie case, Respondent Wurie was apprehended when police witnessed him selling drugs.

when under arrest, police took two Wurie phones. The officers used Wurie’s phone to find an address to an apartment building.

Police investigated the building after getting a warrant and discovered a variety of drugs, drug paraphernalia, guns, and cash. Wurie was arrested and charged with drug possession, as well as rifles and ammunition.

Wurie filed a motion to suppress the evidence before the trial, claiming that the search of the building was unlawful and that the evidence gathered as a result of the search was inadmissible. Wurie’s motion was refused by the trial court.

The appeals court reversed the trial court decision, holding that during searches incident to arrest, cell phones are not objects that fall under an exception to the warrant requirement because cell phones contain a significant amount of personal data.

Issue

whether police can search digital information on a cell phone taken from an arrested person without a warrant.

Rule

In reaching its decision the court applied the Fourth Amendment to the U.S Constitution.

Fourth Amendment (Amendment IV) to the United States Constitution

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects,against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

Reasoning

When applying the law to the facts, the court analyzed the importance of cell phones and the data that they contain.

Court reasoned that police officers could not search digital information on cell phones seized from defendants as a result of their arrests without a warrant.

While the officers may check the physical components of the phones to ensure that they would not be used as weapons, the digital data saved on the phones could not be utilized as a weapon to injure the arresting officers or facilitate the defendants’ escape.

Furthermore, the risk of evidence destruction by remote wiping or data encryption was not demonstrated and could be avoided simply by turning off the phones. Furthermore, the enormous storage capacity of current cell phones raised privacy worries about the amount of data that could be accessible on them.

Holding

No, Police generally may not, without a warrant, search digital information on a cell phone seized from an individual who has been arrested.

Judgment

In Riley’s case, the judgment of the California Court of Appeal reversed and the case remanded for further proceedings non-incontinence of the U.S Supreme court Opinion.

In the Wurie case, the judgment of the First Circuit affirmed.

Concurring Opinion

In a concurring in part and concurring in the judgment, Justice Samuel A. Alito, Jr. voiced concern that the warrantless search exemption following an arrest exists for the exclusive or primary interests of protecting officer safety and preserving evidence.

However, given the privacy concerns at hand, he felt that the majority’s conclusion was the best option. In addition, Justice Alito urged that the legislature create laws that make clear boundaries between when and what information on a phone can be accessed after an arrest.

Obiter dictum

The Court also held that some warrantless searches of cell phones might be permitted in an emergency: when the government’s interests are so compelling that a search would be reasonable.

Read the full opinion here

other case briefs to read

- Marbury versus Madison case brief

- Hamer v Sidway case brief

- Pennoyer v Neff case brief

- Pierson v Post case brief

- Hawkins v Mcgee case brief

- Tinker v des Moines case brief

- Duncan v Louisiana case brief

- Garrett v Dailey case brief

- Lucy v Zehmer case brief

- Brown v Board of education case brief

- Griswold v Connecticut case brief

- Katz v United States case brief

- Leonard v Pepsico case brief

- Wickard v Filburn case brief

- District of Columbia v. Heller case brief

- Gonzales v Raich case brief

- Shelley v Kraemer case brief

- Tennessee v Garner case brief

![How long it takes to become a lawyer? [timeline breakdown] 5 How long it takes to become a lawyer, timeline to become a lawyer, timeline of becoming a lawyer](https://sherianajamii.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/How-long-it-takes-to-become-a-lawyer-768x576.png)