This post all elements of defamation with vivid examples and aid of decided cases.

Understanding the elements of defamation may help you handle any defamation claim successfully.

That may include, knowing everything you need to show or prove to court in a defamation case.

Here I will take you through

- what is defamation

- Elements of defamation

- Examples of defamation/defamatory statements cases

- can Innuendo be defamatory?

- what amount to the publication of a defamatory statement?

- what will not amount to the publication of a defamatory statement?

- publication of a defamatory statement Between the husband and wife

Transform Your Communication, Elevate Your Career!

Ready to take your professional communication skills to new heights? Dive into the world of persuasive business correspondence with my latest book, “From Pen to Profit: The Ultimate Guide to Crafting Persuasive Business Correspondence.”

What You’ll Gain:

Let’s get started.

what is defamation?

Defamation is an act of publishing a defamatory statement that refers to an identifiable person, without lawful justification.

In the case of Sim v. Stretch[mfn]LawTeacher. November 2013. Sim v Stretch – 1936. [online]. Available from: https://www.lawteacher.net/cases/sim-v-stretch.php?vref=1 [Accessed 3 November 2021].[/mfn], Lord Atkin defines a defamatory statement as the statement that injures the reputation of the plaintiff by its tendency to lower him in the estimation of right-thinking members of the society generally or to cause right-thinking members of the society to shun or avoid him.

Generally, the test of Defamation is objective.

That means would an ordinary right-thinking member of society have thought the statement to be defamatory?

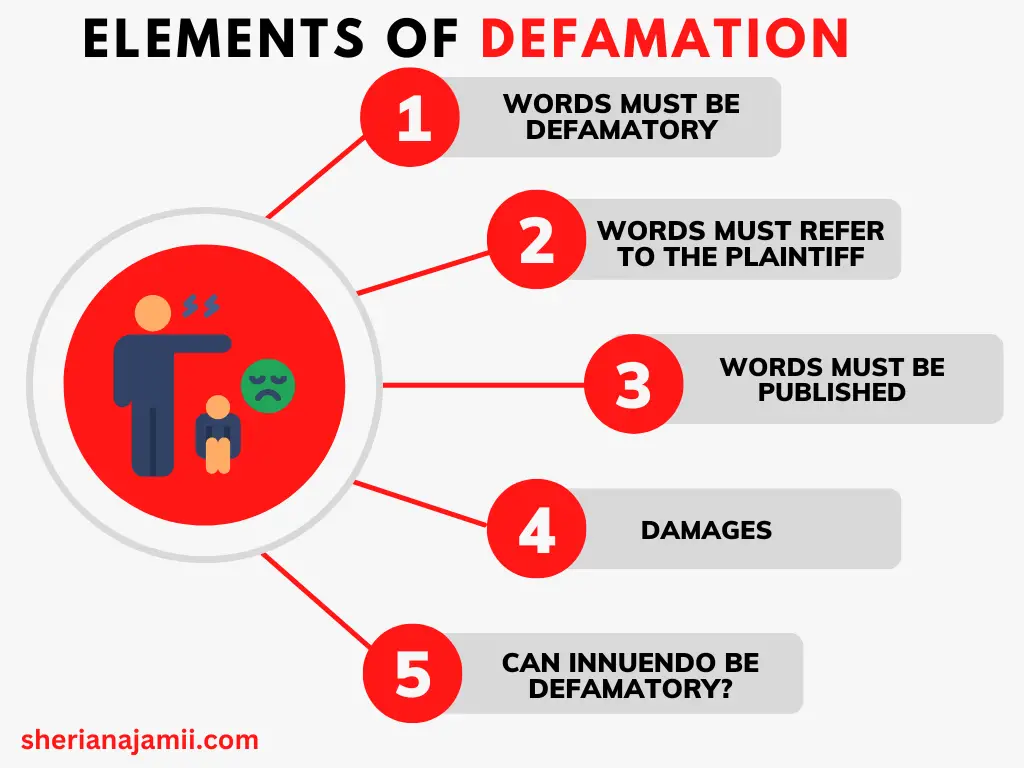

Elements of defamation

The following are the elements of defamation

- The words must be defamatory

- The words must refer to the plaintiff

- The words must be published

- Damages

The words must be defamatory

This is the first element of defamation.

To amount to defamation the words should tend to lower a person in the estimation of other persons or should tend to make them shun or avoid that person.

A statement may also be defamatory if it excites adverse opinions or feelings of other persons against the plaintiff or tends to bring the plaintiff into hatred, contempt, or ridicule, or affects him in his trade, profession, or business.

sometimes the words may not be defamatory in their plain meaning but may become so because of the manner in which they have been spoken.

The manner of pronouncing the words and various other circumstances may explain the meaning of the words.

Is Vulgar abuse defamatory?

the use of vulgar words or vituperative language by a person in anger does not amount to defamation if it only hurts the plaintiff’s pride but does not disparage his reputation.

If, however, it is likely to result in ridicule and humiliation of the plaintiff, an action of defamation would lie.

if the words are written, not spoken, they cannot be protected as mere abuse, for the defendant had time for reflection before he wrote and his leaders may not know the circumstances that may have led him to write what he did.

But it is quite possible for them to be not defamatory for some other reason.

In the case of Thorley v Kerry[mfn](1812) 4 Taunt 355 at 365, and also Pollock CB and Wilde B in Parkins v Scott (1862) 1 H&C 153 at 158, 159). [/mfn] Mansfield CJ stated, “An action may be maintained for words written, for which an action could not be maintained if they were merely spoken”

Statements which reflect on a person’s moral character or professional competence clearly will be defamatory. What is defamatory in one person will not necessarily be so in another.

Examples of defamation/defamatory statements cases

The following are examples of defamatory statements

Cosmos v BBC (1976)

In this case, The BBC broadcast a program giving details about holidays, and the dangers of choosing holidays from glossy brochures. When showing a film of a Cosmos holiday camp in Majorca, they used the music which accompanied a popular series entitled ‘Escape from Colditz’ about a notorious prisoner-of-war camp. Cosmos succeeded in obtaining damages from the BBC.

It was held that the implied meaning of this was that the holiday camp was like a prison camp

Savalas v Associated Newspapers (1976)

In this case Actor Telly Savalas, who played Kojak in the long-running television series of the same name, was awarded £34,000 for being described as ‘a big amiable beast of a man who cannot cope with superstardom’.

Cornwell v Daily Mail (1989)

In this case, actress Charlotte Cornwell successfully sued for a statement made by a columnist that she had ‘a big bum’ and ‘the kind of stage presence that blocks lavatories’.

Stark v Mail on Sunday (1988)

Actress Koo Stark successfully sued the Mail on Sunday for an article headed ‘Koo dated Andy after she wed’, alleging that she still had a ‘lingering love’ for Prince Andrew after she had married the Green Shield Stamp heir Timothy Jeffries.

Keays v New Woman (1989)

Sarah Keays brought a successful libel action against New Woman for an article that included her name with those of ‘two other kisses and tell bimbos’, alleging that she was obsessed with obtaining revenge against MP Cecil Parkinson who was her former employer and the father of her child.

Proetta v Sunday Times (1991)

Carmen Proetta, incensed that the newspaper had accused her of lying and described her as ‘the Tart of Gib’, successfully sued for libel.

Liberace v Daily Mirror (1959)

Musician Liberace was described as ‘the summit of sex, the pinnacle of the masculine, feminine, and neuter … This deadly, winking, sniggering, snuggling, the chromium-plated, scent-impregnated, ice-flavored heap of mother love’.

Liberace was famous before and since for his flamboyant stage act, but he toned down his performances for a time, appearing in a sober suit, and successfully sued for defamation.

Roach v Newsgroup Newspapers Ltd (1992)

It was held to be defamatory to describe the well-known actor who played the part of Ken Barlow in Coronation Street as ‘boring’.

Grappelli v Derek Block Holdings Ltd (1981)

There was no libel in this case, as the words used were likely to excite sympathy rather than disrespect. The musician Stephan Grappelli was described by the defendants as seriously ill and unlikely ever to tour again.

can Innuendo be defamatory?

sometimes a statement may not be defamatory on the face of it but contain an innuendo, which has a defamatory meaning.

Such a statement may be actionable.

For Innuendo to make a statement defamatory the hidden meaning in that statement must be one that could be understood from the words themselves by people who knew the claimant and must be specifically pleaded by the claimant[mfn]Lewis v Daily Telegraph [1964] AC 234[/mfn].

a good example of innuendo is the case of Cassidy v Daily Mirror (1929).

In that case, the claimant was the wife of a man who had been pictured with a young woman at a race meeting and described as engaged to her.

The newspaper reporter had been given that information by Mr. Cassidy and had no reason to doubt his word, but the claimant succeeded in proving an innuendo because the implication was that she would be regarded as a mistress, not a wife.

The words must refer to the plaintiff

This is the second element of defamation.

To amount to defamation the words (or articles) must contain something that to the mind of a reader with knowledge of the relevant circumstances containing defamatory imputations and pointing to the plaintiff as the person defamed.

It is, however, not required that the defamatory statement must have been intended by the defendant to refer to the plaintiff.

liability for libel depends on the fact of defamation and the intention of the defendant is immaterial.

Case law

Hulton & Co. V. Jones (1910) AC 20 or (1909) 2 KB 444

The case related to the publication of a humorous article in the appellant’s newspaper.

The article was concerning a motor festival at Dieppe and contained certain imputations on the morals of Jones described as churchwarden at Peckham and was intended to be a purely fictitious character.

But there happened to be a barrister of this name who was neither a churchwarden nor has taken a part in the festival at Dieppe.

He sued the newspaper proprietors for libel on the ground that his friends believed that the article referred to him.

The House of Lords held the defendants liable by stating that;

A person charged with libel cannot defend himself by showing that he intended not to defame the plaintiff provided that reasonable persons would think the language to be defamatory of the plaintiff.

The statement must identify the claimant, either directly or indirectly.

In Shah vs New Africa Press Ltd (1970) EA 32 it was stated that a defamatory statement need not necessarily name anyone.

It may suggest a person or persons by –for example –their profession, location, or connections.

Can defamation be against a group of people?

The general rule is that if a defamatory statement is made about a class of persons, no action will lie at the suit of an individual who says that the words referred to him.

For example “If a man wrote that all lawyers were thieves, no particular lawyer could sue him unless there was something to point to the particular individual”[mfn]per Willes J in Eastwood v Holmes (1858) 1 F&F 347 at 349).[/mfn]

But if there is something in the words or in the circumstances in which they are published which indicates a particular plaintiff, they may be actionable.

If the class is so small that what is said of the class as a whole necessarily applied to every member of it, then any member of the class can sue.

A defamatory statement against an unspecified member of the class may be actionable if the plaintiff establishes that the defendant meant it for the plaintiff individually.

If a class of people is defamed, there will only be an action available to individual members of that class if they are identifiable as individuals.

If the defendant made a reference to a limited group of people, eg the tenants of a particular building, all will generally be able to sue[mfn]Browne v DC Thomson (1912) SC 359.[/mfn]

Can defamation be accidental?

At common law, it is irrelevant that the defendant did not intend to defame the claimant.

In Hulton & Co vs. Jones (1909) 2 KB 444 the court held that the intention of the defendant is irrelevant in common law in defamation cases where the defendant is liable for a work of fiction that is reasonably understood to refer to the plaintiff, even if the author did not know of his existence.

The words must be published

This is the third element of defamation.

The publication is a communication by the defendant of matters defamatory of the plaintiff to a third party.

There must be a recipient of information other than the plaintiff.

This is because defamation is an injury to one’s reputation, and reputation is what other people think of a man and not his own opinion of himself.

The statement must be published to a person other than the claimant alone.

It is not actionable in civil law merely to make a defamatory statement to the claimant alone out of earshot of a third person, nor to write a letter to the claimant containing defamatory material.

If the claimant decides to show a potentially defamatory letter to someone else, there is a defense of volenti as the claimant, not the defendant, has published the statement.

For example, In Hinderer v Cole (1977), the claimant was sent a letter by his brother-in-law which was addressed to ‘Mr. Stonehouse Hinderer’.

It contained a vicious personal attack on his character, describing him as ‘sick, mean, twisted, vicious, cheap, ugly, filthy, bitter, nasty, hateful, vulgar, loathsome, gnarled, warped, lazy and evil’.

The defamatory words in the letter were shown by the claimant to other people, but the defendant had only sent them to him.

There was therefore no publication by the defendant to a third party, and those words could not form the basis of a libel action.

However, the claimant did obtain damages of £75 because the word ‘Stonehouse’ was held to be defamatory, as it implied that the claimant was like John Stonehouse, an MP who had recently disappeared by faking his death from drowning to escape paying his debts.

if a clerk or typist is given a document containing a defamatory matter for preparing its copies and he returns the same to his employer, it is not publication.

However, dictating a defamatory letter to a typist is probably slander, but when the letter is published to a third party it is libel[mfn]Salmond and Heuston on the Law of Torts, 1996, p154[/mfn].

However, in Bryanston Finance v De Vries [1975] QB 703 it was held that where a letter was written to protect the interests of the business there was a common interest between the employer and employee, and so a letter dictated to a secretary in the normal course of business was protected by qualified privilege.

In Ahern vs. Maguire Chief Baron Brady said that, if a letter ‘however slanderous, is received by the person to whom it is addressed, and does not go beyond him, there is no publication of it in law to support an action for libel’. But a wrongly addressed letter containing defamatory remarks would be actionable if opened by someone other than the subject of the remark.

what amount to the publication of a defamatory statement?

The following situations will amount to publication:

- words are written on a postcard or open message

- defamatory statements placed in an envelope and addressed to the wrong person[mfn]Hebditch v MacIlwaine (1894[/mfn]

- speaking in a loud voice about the claimant so that people nearby can overhear[mfn]White v JF Stone (Lighting and Radio Ltd 1939[/mfn]

- sending a letter to the claimant in circumstances when it is likely to be opened by a third party[mfn]in Pullman v Hill (1891) – a secretary/clerk opened a letter, in Theaker v Richardson (1962) – a husband opened a letter addressed to his wife[/mfn]

- allowing unauthorized defamatory statements to remain on one’s premises[mfn]Byrne v Deane (1937)[/mfn].

- In Cunningham v Essex County Council (2000), it was held that the casual onward transmission of a draft letter in preparation for a reference, alleging criminal proceedings against the claimant, could not attract a defense of qualified privilege. This was an actionable publication for the purposes of a libel claim;

- making a statement that carries the natural consequence of being repeated by someone else[mfn]Slipper v BBC (1991[/mfn].

- In this unusual decision, the defendant was liable not only for the original statement in a television broadcast but for later newspaper reviews that repeated the ‘sting’ of the statement;

- making the statement to the claimant’s spouse;

- a publication on the internet[mfn]Godfrey v Demon Internet Ltd (2000)[/mfn]

what will not amount to the publication of a defamatory statement?

The following situations will not amount to publication:

- placing defamatory material in an unsealed letter[mfn]Huth v Huth (1915)[/mfn]

- making defamatory statements that are later repeated by someone else[mfn]Ward v Weeks (1930)[/mfn].

- This usually breaks the chain of causation and the original maker of the statement will not be liable for repetitions, though there have been exceptions to this[mfn]Slipper v BBC (1991)[/mfn]

- making the statement to one’s own spouse[mfn]Wennhak v Morgan (1888)[/mfn]

- there is some doubt as to whether communications in inter-departmental memos sent or circulated within an organization would be ‘published’.

- Opinion on this was divided in Riddick v Thames Board Mills Ltd (1977).

- In any case, in such situations, there could well be a defense of qualified privilege.

Publication Between the husband and wife

A statement made to one’s own spouse will not be ‘published’ for the purposes of defamation[mfn]Wennhak v Morgan (1888) 20 QBD 635 at 639[/mfn].

Communication between husband and wife is protected as any other rule “might lead to disastrous results to social life”.

Communication of defamatory matters by the wife to the husband and vice versa is not publication.

But the publication of defamatory matters by a third person to a wife about her husband and vice versa will be publication.

Repetition in publication

Every time a defamatory matter is repeated, it is deemed to be a fresh publication and gives a cause of action.

In case of repetition the writer, publisher, editor, etc. are all held liable.

Even the person who disseminates it such as a newsagent or newspaper vendor may be held liable.

But the courts adopt a lenient attitude about such persons.

Such persons can avoid their liability by establishing that they did not know or could not have known by reasonable diligence that they were circulating a matter which was defamatory to someone.

Damages

This is the last and very important element of defamation.

In law, “damages” is another word for the harmed person’s losses resulting from the at-fault party’s actions.

To succeed in any defamation claim the claimant must prove to the court that he suffered damages or some harm due to the published defamatory statement.

This is where the court will redress you.

In defamation cases, the damages may be specific (damages capable of exact calculation) or general damages (damages capable of exact calculation).

Generally defamation damages may include, loss of job, loss of reputation, depression, loss of business, loss of trust, etc.

Read also:

![How long it takes to become a lawyer? [timeline breakdown] 5 How long it takes to become a lawyer, timeline to become a lawyer, timeline of becoming a lawyer](https://sherianajamii.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/How-long-it-takes-to-become-a-lawyer-768x576.png)